November 9, 2011

For the beginning investor, entering the stock market can be a confusing experience. Too often, a newbie dips his or her toe into the water, gets burned, and lets the "pros" take care of money matters from there on out.

It doesn't have to be this way; but first, we need to examine why investing can be such a difficult task.

Peter Senge in his best-seller The Fifth Discipline offers us a simple framework to explain the pitfalls of investing.

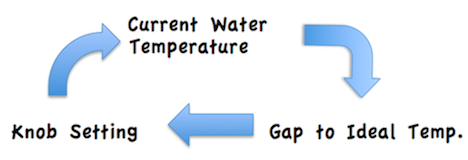

It's all about a feedback delayLet's pretend it's the morning, and you've jumped in the shower. Of course, the water temperature isn't going to be perfect right away; you need to adjust the knob. In the most basic sense, your feedback loop would look like this.

Now let's change things up: You have a defective shower. Instead of the water temperature adjusting almost immediately to a turn in the knob, it takes 10 seconds after turning the knob for any noticeable change to occur.

Now the feedback loop looks like this.

That delay is a pretty big deal, especially if you aren't used to dealing with it. Your first time in the shower might go like this: turn the knob to make it mildly hot, not feel a change, and turn the knob to scalding hot. Ten seconds later, while you're burning your skin off, you turn it to mildly cold. Not feeling a change, you adjust it to frigid cold, and then...

Well, you get the idea.

Applied to investingThe inclusion of a delay causes many a self-inflicted wound, and this explains why some beginners run into trouble.

Enticed into the stock market by opportunities for riches, investors may become frustrated when they don't see immediately results from their decisions. This leads them to constantly move money in and out of certain stocks, never allowing time for their thesis to play out.

In reality, an investor's feedback loop looks like this:

How long of a delay are we talking here?Fool founders Tom and David Gardner have always espoused the view that when investing, the average person should have a three-year time limit, minimum. That doesn't mean that you can't sell a stock before the three-year minimum. If it's crystal clear that your original thesis for investing in a company no longer holds true, then it's best to part ways sooner rather than later.

Being "crystal clear," however, isn't as easy as it sounds. Separating a company's performance as a business from its performance as a stock is essential. As Warren Buffett attributed to mentor Ben Graham in a letter to shareholders, "In the short run, the stock market is a voting machine, but in the long run, it's a weighing machine."

A few choice examples...To illustrate the importance of understanding this delay, I went back and looked at some well-known companies and how they've performed since three years ago, in November 2008. Here's a look:

Company | 3-Year Return | Change at Lowest Close vs. Starting Price |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Foods (Nasdaq: WFM ) | 612% | (15%) |

| Sirius XM (Nasdaq: SIRI ) | 530% | (78%) |

| Green Mountain Coffee (Nasdaq:GMCR ) | 1,200% | 0% |

| Rosetta Stone (NYSE: RST ) | (72%)* | (72%) |

Source: Yahoo! Finance. *Since going public in April 2009.

All four of these examples reveal a slightly different lesson for investors in how they should approach the market with a long-term time horizon.

When the Great Recession hit, investors behaved as if the organic food movement were dead. Adding to the negative sentiment, competition was coming from all sides: Even Wal-Mart (NYSE: WMT ) began offering some organic food. Investors with a three-year horizon, however, realized that eventually, our economy would recover. And if they were following the broader move toward organic food, they knew the trend was undeniable.

Sirius XM, on the other hand, seemed to be on the brink of bankruptcy in early 2009. Believers in the company, however, were confident that the company wasn't going to be going anywhere, anytime soon. When they were bailed out by Liberty Media (Nasdaq: LCAPA ) , life (and cash) was injected back into the company.

I included Green Mountain (maker of the ubiquitous Keurig coffeemakers) to show that there's really no telling how long a delay will be. Sometimes it will be a year, sometimes just one day. In this case, Green Mountain climbed immediately. The bigger point is that three years isgenerally long enough for any delay to work its way out of a system.

Finally, Rosetta Stone is an excellent example of the fact that it is OK to sell a stock before three years if your investment thesis changes dramatically. Just last month, I sold my sharesin this company because of the constant turnover in the executive suite.